Fissure

An anal fissure is a small tear or cut in the lining (mucosa) of the anal canal. These fissures most commonly occur in the posterior midline but can also appear anteriorly. In its acute phase, a fissure may resemble a paper cut, while chronic fissures become deeper, develop fibrous scar tissue, and may be associated with a sentinel pile (a small skin tag) or hypertrophied papilla.

Epidemiology:

- Anal fissures are common in the general population.

- They most frequently affect adults between 15 and 40 years of age, with an equal distribution between men and women.

- In infants, fissures can occur—often related to constipation or irritation—but the causes and healing mechanisms may differ.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Primary Causes:

- Mechanical Trauma: The most frequent trigger is the passage of hard, dry stools that overstretch and tear the delicate anal mucosa.

- Straining during Defecation: Chronic constipation leads to repeated trauma to the anal lining.

- Diarrhea: Frequent, loose stools can also irritate and injure the mucosal lining.

Additional Risk Factors:

- Childbirth: Traumatic delivery can precipitate fissures in women.

- Anal Intercourse: Mechanical stretching during anal sex may increase the risk.

- Inflammatory Conditions: Diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can predispose individuals to fissures.

- Local Ischemia: In older adults, decreased blood flow to the anal region may contribute to fissure formation.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms:

- Pain: A sharp, burning pain typically occurs during and after bowel movements. In acute fissures, this pain is intense and may last for several minutes to hours afterward.

- Bleeding: Bright red blood is often noticed on toilet paper or in the stool.

- Discomfort and Anxiety: Due to the severe pain, patients might develop a fear of defecation, which can further contribute to constipation.

Chronic Fissures:

- Over time, the pain may lessen in intensity but become more persistent.

- A visible skin tag or sentinel pile can develop, indicating chronicity.

Management and Treatment

Conservative (Non-Surgical) Management:

- Dietary Modifications: Increasing fiber intake (via fruits, vegetables, whole grains) and adequate hydration are crucial to soften stools and reduce straining.

- Stool Softeners and Laxatives: These help promote regular, painless bowel movements.

- Sitz Baths: Warm water baths for 10–20 minutes several times a day (especially after bowel movements) help relax the sphincter muscles and alleviate pain.

Topical Medications:

- Anesthetic Creams: Lidocaine or similar agents provide temporary pain relief.

- Vasodilators: Topical nitroglycerin or calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem, nifedipine) help reduce sphincter spasm and improve blood flow to facilitate healing.

- Botulinum Toxin Injections: For fissures that do not respond to topical therapies, injections into the internal anal sphincter can relax the muscle and promote healing.

Surgical Intervention:

- Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy: When conservative measures fail (usually after 6–8 weeks in chronic cases), this procedure involves a controlled division of a portion of the internal sphincter. It is highly effective (with cure rates over 90%) but carries risks such as transient incontinence.

Pathophysiology

- Sphincter Spasm: The internal anal sphincter reacts to the pain by contracting (spasming).

- Reduced Blood Flow: Persistent sphincter spasm decreases blood supply to the affected area, hindering the natural healing process.

- Vicious Cycle: The combination of a tear and sphincter spasm means that every bowel movement can re-injure the fissure, perpetuating the cycle and potentially leading to a chronic fissure.

Diagnosis

Clinical Evaluation:

- History: A detailed account of symptoms, bowel habits, and potential risk factors is obtained.

Physical Examination:

- Visual inspection of the anal area may reveal a linear tear, usually at the posterior midline.

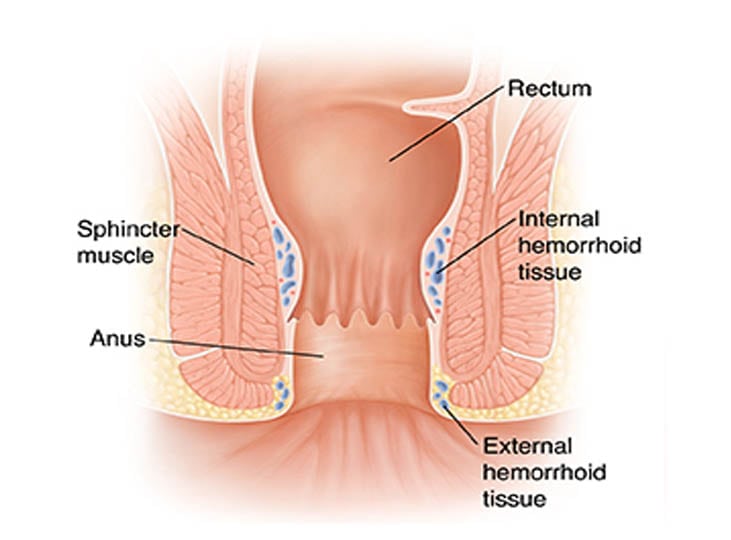

- A gentle digital rectal exam can assess for tenderness and exclude other conditions (e.g., hemorrhoids).

- In some cases, an anoscopic examination is performed for a more detailed view.

Complications and Prognosis

Potential Complications:

- Chronic Fissure: Failure to heal can lead to a persistent, painful lesion.

- Sentinel Pile Formation: Chronic fissures may be accompanied by a skin tag that forms as part of the healing response.

- Anal Stenosis: Scar tissue can narrow the anal canal, making bowel movements more difficult.

- Anal Fistula: In some cases, an abnormal tunnel (fistula) may develop connecting the anal canal to surrounding tissues.

Prognosis:

- Most acute fissures heal within a few weeks with appropriate conservative treatment.

- Chronic fissures are more challenging and may require a combination of medical and surgical therapies.

- Long-term success is largely dependent on correcting underlying bowel habits and preventing constipation.

Prevention

Lifestyle and Dietary Recommendations:

- High-Fiber Diet: Consuming at least 25–35 grams of fiber per day helps maintain soft, regular stools.

- Adequate Hydration: Drinking plenty of fluids (six to eight glasses of water daily) is key.

- Regular Bowel Habits: Avoid delaying bowel movements, which can result in harder stools.

- Proper Anal Hygiene: Gentle cleaning techniques (using soft wipes or water) minimize irritation.

- Avoid Excessive Straining: Using stool softeners and maintaining a healthy diet are essential in preventing recurrence.

Conclusion

Anal fissures represent a common yet often painful anorectal condition. The majority of cases are linked to mechanical trauma from hard stools and can be effectively managed with lifestyle modifications, conservative medical treatments, and, when necessary, surgical intervention. Early diagnosis and appropriate management not only alleviate pain but also prevent chronicity and recurrence. Addressing underlying bowel habits is key to a long-term positive outcome.